From the Open-Publishing Calendar

From the Open-Publishing Newswire

Indybay Feature

Ecuador: Land of Green Palm Farms, Plantation Forests, And Eco-Lodges

Of Forests, Forest Plantations and Zero Net Deforestation vs No Deforestation: The Ecuadorian tropical forest, once hosting an enormous cultural and biological diversity is about to disappear. There's no time for concepts of certified forest exploitation. We hear a lot of concern from palm oil suppliers, manufacturers, and distributors about the “Zero-Deforestation By 2020” Pledge, and the first thing to realize as a consumer, is that the pledge doesn't say that. “Deforestation continues at an alarming rate - 13 million hectares per year, or 36 football fields a minute (7.3 million hectares per year net forest loss taking into account forest restoration and afforestation).”

2008 WWF Pledge of “Zero Net Deforestation by 2020”

2008 WWF Pledge of “Zero Net Deforestation by 2020”

Ecuador: Land of Green Palm Farms, Plantation Forests, And Eco-Lodges

Social conflicts on the way to palm oil plantations in Ecuador have been decades long. Few struggles make it to court and win. Fifteen to twenty years ago, the headlines out of Ecuador sounded the same as in recent years from Sarawak, Sumatra, Malaysia, Indonesia – land grabs, violence, Indigenous struggles, new roads into virgin forests, the smoke and haze from burning mangrove forests (outlawed in 1985 though rarely enforced), mining, drilling, new roads into remote areas, logging, pesticides in the plantations, pesticide drift from US led aerial-spraying in “Plan Colombia” and scores of corrupt political figures - with every outgoing president giving away as much as possible of the country to family and friends.

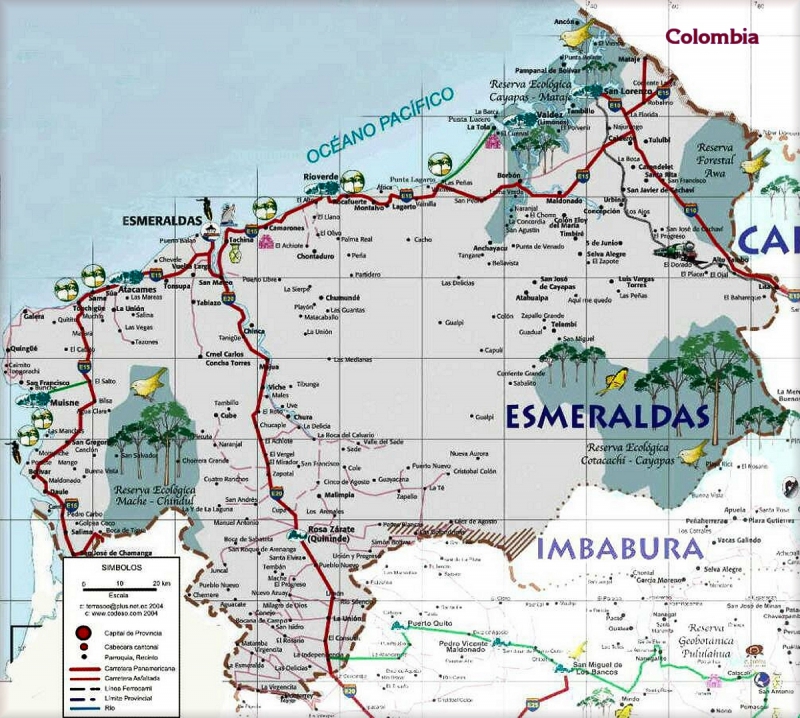

“On 8 August 2002 the Ecuadorian President, Gustavo Noboa issued executive decree 2691, prepared jointly between the ministries of the Environment, Agriculture and Foreign Affairs. This decree designates a 50,000-hectare polygon in the San Lorenzo Canton, Province of Esmeraldas, for agricultural use. Of this area, 5,000 ha are Forestry Heritage of the Ecuadorian State, over 5,000 hectares are Afro-American ancestral lands, and over 1,000 hectares are Awa indigenous lands. Constitutionally and legally, the community lands are indivisible and un-transferable. The undeclared aim of this decree has been to legitimize the systematic expropriation of ancestral and State Forestry Heritage lands, being undertaken over the past years by the palm-growing companies in the north of Esmeraldas. The palm-growers have taken the land away from the communities through illegal purchases and forced displacement of ancestral families. This decree is specifically dedicated to the palm-growers, among which are family members of the out-going President, Gustavo Noboa Bejarano.” “Oil Palm From Cosmetics To Biodiesel Colonization Lives On” (2006)

http://www.terraper.org/web/sites/default/files/publications/1258347774_en.pdf

Logging In Primary Community Forests Of Esmeraldas

The ACEIPA Corporation, which already had a palm oil plantation near Santo Domingo de los Colorados, cleared an additional 5,000 ha of rainforest that adjoins the eastern boundary of Palmeras del Ecuador.

“The development of this new plantation by ACEIPA is another example of the government's indifference to the rights of indigenous peoples. The land that ACEIPA is now clearing had already been recognized by the government as part of the Indians' traditional lands. Although not legally titled to them, it had adjoined the boundaries of their comuna called San Pablo. In 1980 an inter-institutional commission set up by MAG, which included IERAC, agreed that these lands would be included with the San Pablo Comuna. By 1983 all the paper work had been completed and the land had been surveyed and marked with the participation and money of the Siona-Secoya. The Indians were simply waiting for IERAC to finish processing their land title. However, IERAC continued to delay awarding them the title and then, inexplicably, lost all the paperwork related to the Siona-Secoya land. Several people, including some employees at MAG, believe that this action was intentional on the part of IERAC because they knew a change in the administration from Hurtado to Febres-Cordero was coming. Consequently, 5,000 ha of this land now belongs to ACEIPA and is being cleared with the use of heavy military equipment.” (from) African Palm Oil: Impacts in Equador's Amazon (1987)

http://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/ecuador/african-palm-oil-impacts-equadors-amazon

A decade later we can look at the case of a property covering 3,123 hectares known as El Pambilar, allocated to (logging company) Endesa-Botrosa in 1998 by the National Agrarian Development Institute (INDA). “After over two years of violent confrontations between peasants and company staff, complaints and official investigations, in 2000 the Ministry of the Environment confirmed that 90% of the land (2,830 hectares) was located within the State Forestry Heritage (PFE) and had been illegally allocated. The Ministry decided that Endesa-Botrosa must return the land to the State and the Constitutional Tribunal resolved that the peasants should be compensated by the company for the prejudice caused to them. To date (2009), the peasants still wait for any compensation, and some of them like campesino leader Floresmilo Villalta, have been thrown to prison.”

View the “Evaluation of the Forest Management of ENDESA S.A. and Other Lumber Companies of the Peña Durini Group in Ecuador, for Forest Certification by FSC.S.A., Quito Ecuador” (2005) by Accion Ecologica:

http://www.accionecologica.org/index.php?option=com_content&id=545

FSC-Watch 2009 found that “The case of Endesa-Botrosa is symptomatic of key problems of FSC. The logging company did not lose the certificate because of its ongoing destructive logging in primary community forests of Esmeraldas and Pichincha provinces, neither the devastating environmental and social impacts of large scale industrial timber plantations. The reason was because of a technical "detail", the use of a forbidden pesticide. That's how the logic of FSC works."

"FSC Certifying Body (CB) GFA handled the plantation company as a legally independent company, which cannot be blamed for the crimes committed by the other companies of the same Durini group, namely Endesa-Botrosa and Setrafor. The struggle against the Durini Group in Ecuador goes on.”

http://www.fsc-watch.org/archives/2009/09/22/FSC_Friday__2__Suspe

As an important player in the forestry sector, Endesa-Botrosa had been supported for years by a number of public and international organizations, like the federally owned German Technical Cooperation Agency (GTZ) and USAID, and industry financed NGOs like Fundación Natura and its partners WWF, IUCN and The Nature Conservancy (TNC).

All One Forest - From The Redwoods To The Planted Palm Forests (scenic route)

1991. MAXXAM's President, John Seidl, was selected to be Vice Chair of the Board of Directors of The Nature Conservancy. Seidl resigned from MAXXAM in 1992. The Nature Conservancy hired MAXXAM president Dr. John Mick Seidl also of (ENRON) to "protect intact ecosystems and biodiversity hot-spots" around the globe beginning in Costa Rica.

Political connections between ENRON, MAXXAM, Pacific Lumber, The Nature Conservancy, the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation, the Getty Trust, the California UC Regents, and the Gray Davis Administration, are none other than Dr. John M. Seidl - President of ENRON, MAXXAM, Pacific Lumber (PL), and Barry Munitz the Vice President of MAXXAM and PL.

TNC under the premise of “Partnerships To Ensure Environmental Sustainability” and with $8 million dollars from the Moore Foundation sent John Seidl to Costa Rica (with) National Biodiversity Institute (INBio Costa Rica). John M. “Mick” Seidl, was later the Chief Program Officer, Environment, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation - San Francisco, California June 5, 2001 - The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation announced the addition of Dr. John M. "Mick" Seidl as Director for the Foundation's environmental programs. Seidl oversaw, directed and managed the grant administration of the Foundation's environmental programs, which focus on biodiversity and the protection of global intact natural ecosystems.

Dr. John reported directly to Lew Coleman (B of A), the Foundation's President. "With the Foundation's unique approach to grant-making, we stand to make a significant impact through the smart protection, preservation and stewardship of the earth's biodiversity." J. Seidl

News Headlines From Within Ecuador 2004

“The Nature Conservancy Plots With United States Embassy and USAID to Have the Biodiversity Bill Adopted”

http://www.mindfully.org/WTO/2004/The-Nature-Conservancy-Ecuador4mar04.htm

Cecilia Cherrez / Accion Ecologica (Ecuador) wrote:

“On Thursday, 15th January 2004, a meeting was held at the offices of The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in Quito, among national environmental NGOs, Fundación Natura, CEDA, Ecociencia, some of them TNC "partners", besides USAID and the United States Embassy in Ecuador. The objective was to plan a strategy for high-level lobbying, to assign roles and tasks to these organizations, with the aim of putting pressure on the Minister of the Environment and the members of the National Congress to get them to adopt the Biodiversity Bill at the second debate. This Bill will allow privatization of protected areas, disregarding collective rights, enabling transgenic organisms to enter our agricultural system and live organisms to be patented.”

“The United States Embassy representatives in our country, including Ambassador Kristy Kenney and Larry Memmott, head of the Embassy's Economic Sector, have stated that if Ecuador wants to sit at the table in order to negotiate a bilateral free trade agreement, a series of changes must be made in our legislation regarding the environment, biodiversity, intellectual property, labour legislation, and others.”

Alas, the WTO is headquartered in Guayaquil, Ecuador.

For Ecuador though, by 2001 “perhaps the single largest contributor to deforestation in Ecuador were the Agrarian Reform Laws (1964, 1972) which promoted the colonization of vacant (forest) land as the solution to relieve social pressures caused by inequitable (feudal) land distribution, while expanding the agricultural frontier and subsidizing the growth of export-oriented industrial agriculture. The “Green Revolution” was included in the Agrarian Reform package which the U.S. government sponsored throughout Latin America as part of the 'Alliance for Progress' in the 1960’s. The introduction of the Green Revolution technological packet (hybrid seed grown in monocultures, mechanization, chemical fertilizers & pesticides, etc.) has been disastrous in terms of forest removal, soil degradation, contamination from agrotoxics, loss of biodiversity (including native crop varieties and farming knowledge), and growing dependence on external inputs.”

“The Agrarian Reform laws also considered forestland as “unproductive” and thus available for occupation or expropriation. It obliged both property owners (to avoid invasion or expropriation of their land) and colonists (to demonstrate that they were “using” the land as required for claiming title) to clear 50-80% of the forest existing on their holdings. This resulted in the elimination of huge areas of forest to “prove” the land was being utilized. By the time this clause was changed in the early 1990’s most of the Coast has been deforested and unnecessary forest clearing had become (and still is) standard procedure for colonists.”

“Causes And Consequences Of Deforestation In Ecuador” by Jefferson Mecham

Centro de Investigacion de los Bosques Tropicales – CIBT Ecuador - May 2001

http://www.rainforestinfo.org.au/projects/jefferson.htm

Forgotten Times

“For Afro-Ecuadorian communities of Esmeraldas, the agrarian reforms also negatively impacted their traditional collectively held lands. To relieve demographic pressures in other regions, the 1964 and 1973 reforms designated certain areas of Esmeraldas as empty land, and therefore a destination for landless farmers. This designation marked the beginning of an influx of mestizo landless immigrants, known as colonos (colonists or settlers), to the region that would last for decades. Large-scale logging, new highways, and the construction of an oil refinery attracted migrants to the province as well. Colonos arrived from rural areas throughout Ecuador and Colombia, and many came from Manabí, the province located just south of Esmeraldas.”

“These landless immigrants obtained land awarded by the government, sometimes consisting of individual plots of 50 hectares or more. Additionally, colonos purchased ancestral lands that were meant to be communal from individual Afro-descendant families.”

“The legal recognition of Afro-Ecuadorian collective or ancestral titles did not occur as part of the agrarian reforms, so the effect of the government’s titling procedures for colonos was to reduce the amount of land available for Afro-Esmeraldan ancestral communities. In both Esmeraldas and Valle del Chota, land remains at the center of Afro-Ecuadorian communities’ historical and present struggles. Today’s rural Afro-Esmeraldeños fight against

displacement from their land by commercial agriculture, and extractive industries.”

“Forgotten Territories, Unrealized Rights: Rural Afro-Ecuadorians and their Fight for Land, Equality, and Security” November 2009 - A Report from the Rapoport Delegation on Afro-Ecuadorian Land Rights

https://law.utexas.edu/humanrights/projects_and_publications/Ecuador%20Report%20English.pdf

Ecuador Logging and the Oil Palm Industry

The illegal and extra-legal nature of individual sale of communal land means that little empirical data exists to document the trend. “The logging and oil palm industries were first established in Esmeraldas during the 1950s in the centrally located area of Quinindé. The process of clearing land for lumber and installing oil palm plantations has since expanded into northern Esmeraldas and has sharply increased in the early twenty-first century. The logging and oil palm industries are linked together in a way that contributes to the loss of Afro-descendant ancestral territory.”

“In the first of a two-part process, timber companies contracted with middlemen to clear land. Oil palm cultivators soon followed, and, using financial incentives and violence, pressured small farmers to sell or vacate the newly cleared lands. The loss of forests began in the 1960s, and by 1990 approximately ninety percent of Ecuadorian forests west of the Andes Mountains had been logged.”

“Along with indigenous people, Ecuador’s Afro-descendants experience greater poverty and inequality than whites or mestizos, impacting education, and health. Longstanding racial discrimination impacts rural Afro-Ecuadorians’ struggles to remain in their territorial spaces. Structural racism represents a central barrier to the effective guarantee of Afro-Ecuadorians’ human rights. Structural racism, refers not only to direct discrimination based on race, but also to broad social and institutional practices that cause the unequal distribution of resources and social opportunities along racial lines.”

According to the community members that the 2009 Rapoport Delegation on Afro-Ecuadorian Land Rights met with in northern Esmeraldas, “both the palm oil mill effluents (POME, liquid waste) and the air pollution generated by the extraction of palm oil has lead to further environmental degradation, observed by the death of fish populations in nearby rivers, and rashes on the bodies of people who bathe in these waters. At a community forum, the delegation learned specifically of one community that has been severely affected by environmental contamination caused by oil palm cultivation. The community of La Chiquita depends on the river system to eat, drink, bathe, and provide other basic needs; yet, the wastewater from oil palm processing has caused health problems, reduced access to water for consumption and other uses, and inhibited traditional fishing practices.” (“Forgotten Territories, Unrealized Rights: Rural Afro-Ecuadorians and their Fight for Land, Equality, and Security” November 2009 A Report from the Rapoport Delegation on Afro-Ecuadorian Land Rights)

http://www.cornell-landproject.org/download/landgrab2012papers/johnson.pdf

In 2005 the oil palm monoculture expansion in the province of Esmeraldas was 80,000 ha. This represented 38.5 percent of the total area for this crop in Ecuador. The same year for the San Lorenzo canton, oil palm monocultures covered 18,000 ha.

Less than 6 percent remains (broken, polluted, and scattered) of Ecuador's original forests.

What can the consumer assurances of the Certification Industry, and GreenPalm Offsets Certificates, mean? When a product label states that no rainforest is falling today in Ecuador for Organic RSPO Certified Sustainable Palm Oil Products – the agricultural history up 2012-2013 in Ecuador, is riddled with toxic pesticides, indigenous loss of land, food scarcity, (the usual social conflicts and environmental destruction). Logging of virgin forests and road construction are the precursors to drilling for oil, mining, plantations, and settlements.

Cultural Survival puts it this way: “African Palm Oil: Impacts in Equador's Amazon”

http://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/ecuador/african-palm-oil-impacts-equadors-amazon

Speaking of the time period of the 1990's when the pace of Ecuador's deforestation quickened to keep pace along with global competitors: “Fifteen years ago, the areas where the palm oil plantations are now located were trackless virgin rainforest. The forests provide building materials for their homes, wood for canoes, palm leaves and vines for baskets, and a place together wild foods and medicines and to hunt small game. The rivers supply them with water and protein from fish, caimen and turtles.”

“The Indians also depend on extensive areas of rainforest to support their swidden form of agriculture, which is ideally suited to the tropical rainforest. Their small forest gardens, called chakras, use only one to two hectares of land and require no pesticides or fertilizer. A wide variety of crops are planted together rather than in rows. By intercropping these plants, plant-specific pests are controlled and the different root systems avoid competition for nutrients. Finally, this multi-layered garden canopy, which mimics the structure of the surrounding rainforest, helps to break up the impact of the rainfall and minimize erosion. After a couple of years a new garden site is cleared and the old garden is left fallow, allowing the forest to regenerate.”

In the 2004 court case favoring Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadoran Communities: “The beginning of the oil palm industry in Ecuador dates to the late 1950s. However, it is in the 1990s when the oil palm monocultures expanded largely in the Northern provinces. Since then, large-scale oil palm cultivation has critically damaged the local environment as well as having a negative impact on the health of oil palm workers and the community members who are directly exposed to the agrotoxins in their daily water supplies.”

“Within this context, in 2004 two communities (the Awa indigenous community of Guadalito and the Afro-Ecuadorian community of La Chiquita) concerned that the oil palm industry was poisoning their bodies and livelihoods, took legal action against four oil palm companies and the Environment Ministry. The lawsuit was supported by scientific data which demonstrated the contamination of water supplies.”

“Biodiversity loss, food insecurity, soil contamination, soil erosion, deforestation and loss of vegetation cover, surface water pollution and decreased water quality, groundwater pollution or depletion, visible and unknown health impacts, also increases in violence and crime, loss of livelihood.”

August 22, 2014 update: Despite the fact that the Ecuador High Court ruled in favor of the communities, “the Ministry of the Environment has not taken the effective corrective actions demanded by the Court's resolution, specifically those related with the restoration of the contaminated environment as exhorted by the jury. The state has failed to monitor and enforce companies compliance with the law.” (Earth Justice Atlas)

http://ejatlas.org/conflict/guadalito-y-chiquita-against-oil-palm-companies-ecuador

It was nine years after the Ecuador High Court's decision, that there came the 2013 Trafficking in Persons Report from the US State Department stating: “Monoculture oil-palm expansion is also affecting Afro-descendant and indigenous populations in Ecuador; particularly in the biologically diverse Cayapas-Mataje Ecological Reserve in Esmeraldas. Local activists and human rights groups report oil palm companies are increasingly moving into the northern coastal province of Esmeraldas, which is a traditional Afro-Ecuadorian zone. This is having a direct social and environmental impact on Afro-descendant and indigenous Awá and Chachi villages, including land appropriation.”

http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2013/215454.htm

The oil palm saga continues.

“CO2lonialism and the ‘Unintended Consequences’ of Commoditizing Climate Change: Geographies of Hope Amid a Sea of Oil Palms in the Northwest Pacific Frontier Territory-Region of Ecuador”

“Development projects surround and infiltrate the Indigenous and Afro-ecuadorian ancestral territories of the canton of San Lorenzo (Esmeraldas Province), located in the “Northwest Pacific Fronter Territory-region of Ecuador.”

In "Geographies Of CO2lonialism And Hope In The Northwest Pacific Frontier Territory-Region Of Ecuador" (2010) author Julianne Adams Hazlewood asks the question “to what degree the Ecuadorian state’s support and investment in oil palm plantation expansion designed to meet biofuel crop demands in the coastal rainforest regions, results in the rearrangement, and often times, devastation of Indigenous Awá and Chachi and Afro-ecuadorian communities’ natural and human geographies. It also inquires into the Ecuadorian government’s recently approved (October 2008) state level conservation incentives project called Socio-Bosque (Forest Partners) developed to do the following: protect the rainforests and its ecological services, alleviate poverty in rural areas, and position the country as an ‘environmental world leader’ for taking concrete actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from avoided deforestation. Socio Bosque claims to be progressive and even revolutionary, but may enact new forms of exploitation and governance in Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian territories that are specific to time and place, but are enduringly colonial.”

“Nevertheless, (Geographies Of CO2lonialism And Hope) also highlights geographies of hope by demonstrating that, contrary to the surrounding sea of monoculture oil palm plantations and the CO2lonial air of contradictory laws in relation to biofuel and ecological services development, Awá, Chachi, and Afro-Ecuadorian communities maintain sustainable practices and enhance agricultural diversity within their territories. Additionally, it emphasizes the emergent place-based social movements in relation to defense of their territories and identities; Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian communities avoid conflict pressures by creating interethnic networks. By casting social nets between their territories, their communities stay connected and, together, defend their rights to territorial self-determination and Living Well and the Rights of Nature.”

Some Chapter headings in this very personal account from inside Ecuador:

“Geographies of Terror and Violence and Research, Hope, and Responsibility; Geographies of Hope: Establishing a Territory of Peace; Casting Inter-ethnic Social Nets across a Sea of Oil Palms in the Northwest Pacific Territory-region of Ecuador.”

“Communities surrounded and infringed upon by development processes, in this case, oil palm plantations, choose to assert themselves in a particular way and take on a certain identity, or perform as agents of transculturation to take action to make a change in their lives and negotiate development (and conservation) schemes. In order to do so, they often make claim to a certain essentialized ancestral identity, although the lifeworld they are drawing from inevitably has much deeper roots, and thus, various routes that are much more complex and complicated. It is at the crossroads of these roots and routes where people rise up and defend what they call home.”

“Hybrid networking these crossroads or hybridizations of active negotiations, can emphasize a ‘relational becoming’, but in order to be effective, must be put into actions that lead towards actual laws, structures, and law-supporting practices that reinforce the “struggles of the poor” and help them defend themselves against geographies of violence, terror, and fear that are implemented via oil palm plantation expansion. Geographies of hope, then, necessarily work towards an increase in a rights-based consciousness and practices basically because it has to.”

“Unfortunately, immersed in geographies of terror and violence, communities inspired by revolutionary impulses need state and international support to stand up to multinational geopolitical interests. In looking at geographies of hope as peace-with-justice processes, they obligate implementation of these rights by establishing laws and structures that actually respect rights, such as the constitutional rights of the right to Living Well, Plurinationality, and the rights of Nature (2008 Ecuador Constitution).”

Julianne Adams Hazlewood, "Geographies Of CO2lonialism And Hope In The Northwest Pacific Frontier Territory-Region Of Ecuador" (2010) 321 pages

http://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/52/

Click on download link to view as PDF. The file is 240 MB. Footnotes and extensive citations of descriptive content make up half the document, great images.

Much of what is documented by the author may by contrast, help to explain more clearly, the similar claims of oil palm products manufacturers and distributors of palm oil products that assure us: “The region in Ecuador where our Organic Red Palm Oil is grown has numerous small family farms, averaging 10 hectares (about 25 acres), interspersed throughout the regional forests. These subsistence farms were planted many years ago and are now being worked by second and third generation farming families. Palm oil grown in Southeast Asia is associated with destruction of rainforest and orangutan habitat. It is important to note that orangutans do not live in Ecuador and our red palm does not contribute to deforestation or habitat destruction.”

Interesting enough, the farming families (smallholders, smallholder farmers) are usually surrounded by, and even can be part of the legal oil palm plantation real estate network of expansion (defined so well in the Indonesian smallholder law passed months before Jacowi ascended to the Presidency). That a different interpretation of colonialism appears in different countries where palm oil cultivation continues to expand rapidly, appears to be a function of dominant culture national interpretation, International cultural exchange, national political instability, local NGO's, Indigenous cultures persistence, global trade agendas, and market function.

“Modern oil palm cultivation is generally characterized by large monocultures of uniform age structure, low canopy, sparse undergrowth, a low-stability microclimate and intensive use of fertilizers and pesticides. The oil palm tree generates fruits from the third year, with yield per tree increasing gradually until it peaks at approximately 20 years. Hence, oil palm plantations are typically destroyed and replanted at 25 to 30 year intervals. The process of palm oil production tends to reduce freshwater and soil quality, and adversely affects local communities which are dependent on ecosystem products (such as food and medicines) and ecosystem services (such as regulation of the hydrological cycle and soil protection) provided by the forests.” Taken from: “Oil Palm Plantations: Threats And Opportunities For Tropical Ecosystems - Thematic Focus: Ecosystem Management and Resource Efficiency” - UNEP Global Environmental Alert Service (GEAS) December 2011

http://www.unep.org/pdf/Dec_11_Palm_Plantations.pdf

Size of Farm, Market Destination, Land Use Changes in Ecuador

The size of small farms or smallholder farms varies as generations of family members remain, the original 'smallholding' is sub-divided, and allowing for the crops to be grown.

“Ninety-eight percent of the coffee in Ecuador is grown by small-scale farmers. Most Ecuadorian coffee is grown on small farms, from 1 to 10 hectares. About half of the coffee land is planted in coffee alone, while the rest is co-planted with cacao, citrus fruits, bananas, and often mangoes. Historically, coffee was one of the most important crops in Ecuador. However, starting in the 1970s, the government increased investments in the oil and banana industries. In the late 1980s, when the world price for coffee began to drop, government support was pulled back even further. Coffee farmers could no longer support their families and began abandoning their farms to look for jobs in the cities. Many migrated to Spain, Italy and the U.S.”

http://www.equalexchange.coop/history-of-coffee-in-ecuador

Known for its biological diversity, the Choco is one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet. The Ecuadorian part of this ecosystem, is known as one of the world's biological "Hotspots." Of the original forest extent, estimated at 80,000 square kilometers, only 6 percent is left, spread out, west of Ecuador's Western Andes, and lying mainly on the northern edge of Esmeraldas province.

The devastation of these forests was due, in large part, to the growth of agriculture on the coast, starting in the early decades of the twentieth century and, during the last four decades (1960-2000) due to logging. The rate of destruction has made these forests the most devastated in Ecuador.

Another key document of history and research paper of that era was "The Bitter Fruit of Oil Palm" The case of Ecuador: Paradise in Seven Years? by Ricardo Buitrón (2000)

http://www.wrm.org.uy/oldsite/plantations/material/oilpalm3.html

Ricardo Buitron states: “By the end of 1999, plantations in the district of San Lorenzo in the province of Esmeraldas had expanded by more than 15,000 ha. The Ministry of Environment reports that 8,000 ha of forest has been destroyed in this area by palm plantations, and anticipates that in the following years over 30,000 ha more will fall to the plantations. The area dedicated to African palm monoculture in the North of Esmeraldas is variously reported by former authorities of the area as being 60,000 to 100,000 hectares (El Comercio 30/03/99).”

“In San Lorenzo, in the North of the province of Esmeraldas, an unprecedented amount of land has changed hands over the past several years. Land is bought by dealers at absurdly low prices and then sold to palm cultivation companies at a higher price. In other cases, especially in the area of Recaurte in the same province, these companies buy land directly from farmers at even lower prices than those paid by land dealers. Through these mechanisms, the companies have been able to take over peasants’ land at the same time they occupy over 60,000 hectares of state-owned forest areas. Some of this land is now in the hands of the brother of former president Jamil Mahuad Witt and the president of the National Congress, Juan José Pons Arízaga (La Hora 16/03/2000)”

1) There are companies that are vertically integrated with the main national and international corporate groups involved in growing, processing and trading oil palm products: Large plantations – 10,000 hectares, 14000 hectares, 20,000 hectares.

2) Second, independent producers handling plantations of 250 to 1000 hectares in size, settled in the provinces of Esmeraldas and Pichincha.

3) Third, small agricultural producers cultivating less than 150 hectares, who are subject to the prices imposed on their products by the big firms. This sector only receives what is left over after the monopolistic groups have taken what they can get.

“Oil palm companies have also recently moved into the northern area of Esmeraldas. This migration to the north of Ecuador's coastal region has been caused by a decreased yield in oil palm plantations in the areas of Santo Domingo and Quinindé. According to ANCUPA representatives, due to "environmental causes and poor nutritional management", yields have fallen by 25 percent and plantations are in such bad shape in the areas of Quinindé, Quevedo and Santo Domingo, that recovery is not possible (El Comercio 11/03/99). New lands are thus needed for oil palm monoculture.”

“Heavy use of insecticides, fungicides and herbicides. Those most widely used are: endosulfan (organochlorinated) and carbofuran (carbamate, forbidden in the United States and Canada), malathion (organophosphate); the most widely used herbicide is glyphosate; while carboxin is the most common fungicide (Nuñez 1998). These insecticides used have been classified as highly and moderately dangerous by the World Health Organization. These companies also use chemical fertilizers. All this has led to water contamination. Water sampling in palm-growing zones in Pichincha near Santo Domingo show that chemical concentrations exceed the limits recommended for human or livestock consumption. They are also too high for irrigation and the support of aquatic life (Nuñez 1998). In addition to affecting the health of agricultural workers and people who live near plantations, agro-chemical contamination has brought about:

1) Contamination and destruction of river life. The use of river and stream water to prepare and wash the equipment for applying chemicals periodically kills fish and other aquatic life. Waste from palm extraction factories containing high-fat residues meanwhile alters the oxygen concentration of the water.

2) Deterioration of the health of domestic animals and wildlife near the plantations. The inhabitants of Santo Domingo de los Colorados report the disappearance of fish species, such as guañas (Chaetostoma aequinoctialis), barbudos (Rhamdia wagneri), ….”

“In the province of Esmeraldas the hope is that in seven years, when current plans for oil palm plantations have been completely implemented, the local population will benefit through increased employment, welfare and prosperity.”

“Oil palm monoculture, like other export-oriented agro-industrial activities, responds to the production logic of a model that privileges environmental destruction, over-exploitation of natural resources, and the cultural destruction of indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian populations.”

Today, organic palm oil is sourced from small farms in the Esmereldas, and the Esmeraldas coast is dotted with Eco-lodges and shrimp farms.

Though, even by conservative estimates, 15 years ago, “over 70% of the coastal mangroves had been eliminated by the shrimp industry, which also moved into Esmeraldas threatening the Earth’s tallest and best conserved mangrove ecosystem and the traditional fishing communities which depend upon it for their subsistence.” (excerpt) "Causes And Consequences Of Deforestation In Ecuador" by Jefferson Mecham; Centro de Investigacion de los Bosques Tropicales – CIBT Ecuador - May 2001

http://www.rainforestinfo.org.au/projects/jefferson.htm

“Over the last several decades, a large percentage of coastal mangrove wetland forests in Ecuador have been cleared for the development of shrimp aquaculture despite the existence of forestry laws protecting mangroves since the mid 1980s. The current Ecuadorian Forestry Law stipulates that mangroves are public goods of the State, "not subject to possession or any other kind of appropriation, and can only be exploited by way of authorized concession."

“Since 1985, the cutting, burning, and exploitation of mangroves has been prohibited. These policies were weakly upheld in light of export-led growth and global demand for cheap shrimp cocktail that drove the conversion of public mangrove areas into private shrimp farms throughout Ecuador and many other parts of the developing world, resulting in widespread environmental degradation, welfare impacts, and social conflict and what has called a "tragedy of enclosures. However, in 1999, White Spot Syndrome Virus, a disease in cultured shrimp, halted the further expansion of shrimp ponds into vital mangrove habitat. By the year 2000, the Ecuadorian State began to recognize the ancestral rights of "traditional user groups" to mangrove resources, paving the way for custodias, ten-year community-managed concessions.”

“As of July 2011, a total of 37,818 hectares have been granted to 41 different communities as part of the national strategy toward community-based conservation and management of mangrove resources. After decades of struggle and conflict between shrimp farmers and artisanal fishers who have lost their fishing grounds to aquaculture, fishing communities in Ecuador now have the legal backing to defend their livelihoods, guard their mangroves against further destruction, and promote sustainable mangrove fisheries. However, the establishment of custodias has changed the nature of the struggle over mangrove resources from artisanal fishers versus shrimp farmers to a struggle between compañeros, those who have custodias and those who do not.” Shifting Policies, Access, And The Tragedy Of Enclosures In Ecuadorian Mangrove Fisheries: Towards A Political Ecology Of The Commons (2011)

“In Ecuador, the industry started in the late 1960s and rapidly grew. By 1999, 175,255 hectares of land had been converted to shrimp farms. That year, Ecuador was the fourth largest shrimp producer in the world, and the largest in the Western Hemisphere, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Ecuador’s mangrove forests declined as shrimp farming and other coastal development occurred, salt flats or salt marshes on slightly higher ground have also been converted.”

http://www.earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=6918

“Cockles In Custody: The Role Of Common Property Arrangements In The Ecological Sustainability Of Mangrove Fisheries On The Ecuadorian Coast” (2011) Christine M. Beitl

https://www.thecommonsjournal.org/index.php/ijc/article/view/URN%3ANBN%3ANL%3AUI%3A10-1-101644

One may select HTML or PDF full text versions for viewing.

In “Cockles In Custody: The Role Of Common Property Arrangements In The Ecological Sustainability Of Mangrove Fisheries On The Ecuadorian Coast” Christine M. Beitl investigates how common property institutional arrangements contribute to sustainable mangrove fisheries in coastal Ecuador, focusing on the fishery for the mangrove cockle, a bivalve mollusk harvested from the roots of mangrove trees and of particular social, economic, and cultural importance for the communities that depend on it. Specifically, this study examines the emergence of new civil society institutions within the historical context of extensive mangrove deforestation for the expansion of shrimp farming, policy changes in the late 1990s that recognized “ancestral” rights of local communities to mangrove resources, and how custodias, community-managed mangrove concessions, affect the cockle fishery. Findings from interviews with shell collectors and analysis of catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE) indicate that mangrove concessions as common property regimes promote community empowerment, local autonomy over resources, mangrove conservation and recovery, higher cockle catch shares, and larger shell sizes, but the benefits are not evenly distributed. Associations without custodias and independent cockle collectors feel further marginalized by the loss of gathering grounds, potentially deflecting problems of over-exploitation to “open-access” areas, in which mangrove fisheries are weakly managed by the State.”

“While the deforestation rates of mangroves are generally decreasing, they still remain significantly higher than other forest types (FAO 2005). According to Valiela et al. (2001), mariculture contributes to about 52% of global mangrove loss and shrimp farming is the most significant type of aquaculture associated with mangrove deforestation. The vulnerability of mangroves to destruction further reflects global policies and institutions that have favored export-oriented development like shrimp farming over local tradeoffs. While shrimp mariculture offers the potential for economic development by increasing export earnings and generating employment in urban centers, the local reality in marginalized coastal communities has been dramatic landscape change and decreasing water quality. Along with ecological degradation, mangrove deforestation has also resulted in numerous social impacts such as community displacement, the loss of livelihoods, the erosion of resource rights, the reorganization of local economies, and an increase in economic disparity and social conflict. In some places around the world, including Ecuador, resistance movements have emerged in defense of mangroves.”

Extensive published research is cited throughout “In “Cockles In Custody: The Role Of Common Property Arrangements In The Ecological Sustainability Of Mangrove Fisheries On The Ecuadorian Coast” with dates from every year up to 2011.

“Nature retaliated against the intensive shrimp farms. Shrimp diseases and floods, formerly prevented in part by the natural filtration and buffering of the mangrove ecosystem, became rampant; making environmentally sustainable farms a better long-term economic investment. After the first, glorious, get-rich-quick days, the industry was plagued by the kind of spectacular crashes that tend to dog this intensive form of mono-culture. In his 1995 Shrimp News International annual report, Rosenberry's account of the world shrimp industry reads like a disease almanac. Shrimp farmers in Western countries battled Taura Syndrome, and Asian ones fended off the yellowhead virus and the white spot virus, which attacked India's ponds just as the villagers were protesting. Last May, when Taura Syndrome, a virus from Ecuador, reached three big shrimp farms in Texas, it rapidly killed a $10 million crop.”

http://www.motherjones.com/politics/1996/03/rainforest-shrimp

Just do your part - the prawns are deep fried at restaurants around the world in a blend of canola and palm oil generally, just like at Wendys and McDonalds. Oh, your part, is to change your diet.

Of Forests, Forest Plantations and Zero Net Deforestation vs No Deforestation

“FAO developed the official definition of ‘forests’ which declares that 'forest includes natural forests and forest plantations. It is used to refer to land with a tree canopy cover of more than 10 percent and area of more than 0.5 ha'. On this basis, the definition established two categories of forests: natural forests and plantation forests. Many NGOs and indigenous peoples contested this definition and have insisted that there should be a clear distinction between forests and plantations. They do not accept that plantations are forests - the only thing in common between the two is the fact that both have trees. Other than that, they are two totally different systems. A forest is a complex, self-regenerating system, encompassing soil, water, microclimate, energy, and a wide variety of plants and animals in a mutual relationship. Plantations, on the other hand, have one or a few species of trees/crops (often alien), planted in homogenous blocks of the same age. Plantation trees are much closer to industrial agricultural crops or a traditional agricultural field than to forests as usually understood.”

“This distinction is important because including plantations as forests is accepting that this is a forest ecosystem, which clearly it is not, secondly, this obscures the real rate of deforestation, and thirdly, it virtually casts a blind eye to the adverse social and environmental impacts of plantations, especially on indigenous peoples. Therefore, it has been recommended that "natural forests" be simply called forests (primary and secondary) and "forest plantations" be called tree plantations.” (Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues - Sixth session - New York, 14-25 May 2007 “Oil Palm and Other Commercial Tree Plantations, Monocropping: Impacts on Indigenous Peoples’ Land Tenure and Resource Management Systems and Livelihoods”)

World Wildlife Fund Calls For Zero-Deforestation Pledge (not!)

In May 2008, at the Ninth Conference of Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP9) in Bonn, delegates of 68 countries - including Ecuador - pledged support for WWF's call for zero net deforestation by 2020.

http://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwf_2020_zero_net_deforest_brief.pdf

“Zero Net Deforestation” can be distinguished from "Zero Deforestation", which means no deforestation anywhere.”

The example below rationalizes in unspoken trade-offs the rural poverty, institutional racism (structural racism) built into the system, loss of land, dispossession, lack of enforcement of protected areas, and the effort shift to new areas of forest recently cleared for new grazing territories.

"Zero net deforestation acknowledges that some forest loss could be offset by forest restoration. Zero net deforestation is not synonymous with a total prohibition on forest clearing. Rather, it leaves room for change in the configuration of the land-use mosaic, provided the net quantity, quality and carbon density of forests is maintained. It recognizes that, in some circumstances, conversion of forests in one site may contribute to the sustainable development and conservation of the wider landscape (e.g. reducing livestock grazing in a protected area may require conversion of forest areas in the buffer zone to provide farmland to local communities).”

”Plantations, particularly intensively-managed, industrial plantations can contribute disproportionately to future demands. However, these fastwood plantations are controversial; much of their expansion has come from the conversion of natural forests and other areas of high conservation values such as grasslands and wetlands. Their establishment has in many cases also resulted in significant social consequences due to a disregard for the rights and interests of local communities.”

The Consumer Goods Forum (CGF), a group of the world’s 400 largest consumer goods companies from 70 countries, announced their commitment to "source only deforestation-free commodities in their supply chains and help achieve net-zero deforestation by 2020."

http://www.theconsumergoodsforum.com/sustainability-strategic-focus/sustainability-resolutions/deforestation-resolution

The Tropical Forest Alliance (TFA) 2020, a public-private partnership (PPP) was established in 2012 at the Rio+20 Summit, to provide guidance on how to implement the forum’s pledge. The CGF pledge group boasts combined annual sales of more than $3 trillion, and includes leading brands such as Unilever, Johnson & Johnson, Walmart, and IKEA.

http://www.tfa2020.com/index.php/about-tfa2020

Zero-Deforestation vs No-Deforestation vs Deforestation-Free

The “No-deforestation policy” by definition, according to Greenpeace, “is no human induced conversion of natural forests, with the exclusion of small-scale low intensity subsistence conversion. Only degraded forest lands that are not High Carbon Stock, High Conservation Value, or peatlands may be converted to non-forest, it also involves the active conservation, protection, and if necessary, restoration of natural forests by those who control and/or manage them.”

For industry, there are two different target approaches to Zero-Deforestation;

-One is gross which equates the reduction of deforestation of native forests to the increase in the establishment of new forests on previously cleared lands (reforestation).

-While net deforestation inherently equates the value of protecting native forests with that of planted forests.

“Deforestation continues at an alarming rate − 13 million hectares per year, or 36 football fields a minute (7.3 million hectares per year net forest loss taking into account forest restoration and afforestation).” 2008 WWF Zero Net Deforestation by 2020

The Ecuadorian tropical forest, once hosting an enormous cultural and biological diversity is about to disappear. There's no time for concepts of certified forest exploitation. Sustainable Palm Oil, oh yes, it is all that.

Tomas DiFiore

By invoking the 'Copyright Disclaimer' Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for "fair use" for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favor of fair use."

§ 107. Limitations on exclusive rights- Fair use: Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

If you or anyone wish to use copyrighted material from this article for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Tomas DiFiore

Esmeraldas, Forest Plantations, Forests, Logging In Primary Community Forests, No Deforestation, Zero Net Deforestation, Zero-Deforestation Pledge,

Social conflicts on the way to palm oil plantations in Ecuador have been decades long. Few struggles make it to court and win. Fifteen to twenty years ago, the headlines out of Ecuador sounded the same as in recent years from Sarawak, Sumatra, Malaysia, Indonesia – land grabs, violence, Indigenous struggles, new roads into virgin forests, the smoke and haze from burning mangrove forests (outlawed in 1985 though rarely enforced), mining, drilling, new roads into remote areas, logging, pesticides in the plantations, pesticide drift from US led aerial-spraying in “Plan Colombia” and scores of corrupt political figures - with every outgoing president giving away as much as possible of the country to family and friends.

“On 8 August 2002 the Ecuadorian President, Gustavo Noboa issued executive decree 2691, prepared jointly between the ministries of the Environment, Agriculture and Foreign Affairs. This decree designates a 50,000-hectare polygon in the San Lorenzo Canton, Province of Esmeraldas, for agricultural use. Of this area, 5,000 ha are Forestry Heritage of the Ecuadorian State, over 5,000 hectares are Afro-American ancestral lands, and over 1,000 hectares are Awa indigenous lands. Constitutionally and legally, the community lands are indivisible and un-transferable. The undeclared aim of this decree has been to legitimize the systematic expropriation of ancestral and State Forestry Heritage lands, being undertaken over the past years by the palm-growing companies in the north of Esmeraldas. The palm-growers have taken the land away from the communities through illegal purchases and forced displacement of ancestral families. This decree is specifically dedicated to the palm-growers, among which are family members of the out-going President, Gustavo Noboa Bejarano.” “Oil Palm From Cosmetics To Biodiesel Colonization Lives On” (2006)

http://www.terraper.org/web/sites/default/files/publications/1258347774_en.pdf

Logging In Primary Community Forests Of Esmeraldas

The ACEIPA Corporation, which already had a palm oil plantation near Santo Domingo de los Colorados, cleared an additional 5,000 ha of rainforest that adjoins the eastern boundary of Palmeras del Ecuador.

“The development of this new plantation by ACEIPA is another example of the government's indifference to the rights of indigenous peoples. The land that ACEIPA is now clearing had already been recognized by the government as part of the Indians' traditional lands. Although not legally titled to them, it had adjoined the boundaries of their comuna called San Pablo. In 1980 an inter-institutional commission set up by MAG, which included IERAC, agreed that these lands would be included with the San Pablo Comuna. By 1983 all the paper work had been completed and the land had been surveyed and marked with the participation and money of the Siona-Secoya. The Indians were simply waiting for IERAC to finish processing their land title. However, IERAC continued to delay awarding them the title and then, inexplicably, lost all the paperwork related to the Siona-Secoya land. Several people, including some employees at MAG, believe that this action was intentional on the part of IERAC because they knew a change in the administration from Hurtado to Febres-Cordero was coming. Consequently, 5,000 ha of this land now belongs to ACEIPA and is being cleared with the use of heavy military equipment.” (from) African Palm Oil: Impacts in Equador's Amazon (1987)

http://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/ecuador/african-palm-oil-impacts-equadors-amazon

A decade later we can look at the case of a property covering 3,123 hectares known as El Pambilar, allocated to (logging company) Endesa-Botrosa in 1998 by the National Agrarian Development Institute (INDA). “After over two years of violent confrontations between peasants and company staff, complaints and official investigations, in 2000 the Ministry of the Environment confirmed that 90% of the land (2,830 hectares) was located within the State Forestry Heritage (PFE) and had been illegally allocated. The Ministry decided that Endesa-Botrosa must return the land to the State and the Constitutional Tribunal resolved that the peasants should be compensated by the company for the prejudice caused to them. To date (2009), the peasants still wait for any compensation, and some of them like campesino leader Floresmilo Villalta, have been thrown to prison.”

View the “Evaluation of the Forest Management of ENDESA S.A. and Other Lumber Companies of the Peña Durini Group in Ecuador, for Forest Certification by FSC.S.A., Quito Ecuador” (2005) by Accion Ecologica:

http://www.accionecologica.org/index.php?option=com_content&id=545

FSC-Watch 2009 found that “The case of Endesa-Botrosa is symptomatic of key problems of FSC. The logging company did not lose the certificate because of its ongoing destructive logging in primary community forests of Esmeraldas and Pichincha provinces, neither the devastating environmental and social impacts of large scale industrial timber plantations. The reason was because of a technical "detail", the use of a forbidden pesticide. That's how the logic of FSC works."

"FSC Certifying Body (CB) GFA handled the plantation company as a legally independent company, which cannot be blamed for the crimes committed by the other companies of the same Durini group, namely Endesa-Botrosa and Setrafor. The struggle against the Durini Group in Ecuador goes on.”

http://www.fsc-watch.org/archives/2009/09/22/FSC_Friday__2__Suspe

As an important player in the forestry sector, Endesa-Botrosa had been supported for years by a number of public and international organizations, like the federally owned German Technical Cooperation Agency (GTZ) and USAID, and industry financed NGOs like Fundación Natura and its partners WWF, IUCN and The Nature Conservancy (TNC).

All One Forest - From The Redwoods To The Planted Palm Forests (scenic route)

1991. MAXXAM's President, John Seidl, was selected to be Vice Chair of the Board of Directors of The Nature Conservancy. Seidl resigned from MAXXAM in 1992. The Nature Conservancy hired MAXXAM president Dr. John Mick Seidl also of (ENRON) to "protect intact ecosystems and biodiversity hot-spots" around the globe beginning in Costa Rica.

Political connections between ENRON, MAXXAM, Pacific Lumber, The Nature Conservancy, the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation, the Getty Trust, the California UC Regents, and the Gray Davis Administration, are none other than Dr. John M. Seidl - President of ENRON, MAXXAM, Pacific Lumber (PL), and Barry Munitz the Vice President of MAXXAM and PL.

TNC under the premise of “Partnerships To Ensure Environmental Sustainability” and with $8 million dollars from the Moore Foundation sent John Seidl to Costa Rica (with) National Biodiversity Institute (INBio Costa Rica). John M. “Mick” Seidl, was later the Chief Program Officer, Environment, of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation - San Francisco, California June 5, 2001 - The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation announced the addition of Dr. John M. "Mick" Seidl as Director for the Foundation's environmental programs. Seidl oversaw, directed and managed the grant administration of the Foundation's environmental programs, which focus on biodiversity and the protection of global intact natural ecosystems.

Dr. John reported directly to Lew Coleman (B of A), the Foundation's President. "With the Foundation's unique approach to grant-making, we stand to make a significant impact through the smart protection, preservation and stewardship of the earth's biodiversity." J. Seidl

News Headlines From Within Ecuador 2004

“The Nature Conservancy Plots With United States Embassy and USAID to Have the Biodiversity Bill Adopted”

http://www.mindfully.org/WTO/2004/The-Nature-Conservancy-Ecuador4mar04.htm

Cecilia Cherrez / Accion Ecologica (Ecuador) wrote:

“On Thursday, 15th January 2004, a meeting was held at the offices of The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in Quito, among national environmental NGOs, Fundación Natura, CEDA, Ecociencia, some of them TNC "partners", besides USAID and the United States Embassy in Ecuador. The objective was to plan a strategy for high-level lobbying, to assign roles and tasks to these organizations, with the aim of putting pressure on the Minister of the Environment and the members of the National Congress to get them to adopt the Biodiversity Bill at the second debate. This Bill will allow privatization of protected areas, disregarding collective rights, enabling transgenic organisms to enter our agricultural system and live organisms to be patented.”

“The United States Embassy representatives in our country, including Ambassador Kristy Kenney and Larry Memmott, head of the Embassy's Economic Sector, have stated that if Ecuador wants to sit at the table in order to negotiate a bilateral free trade agreement, a series of changes must be made in our legislation regarding the environment, biodiversity, intellectual property, labour legislation, and others.”

Alas, the WTO is headquartered in Guayaquil, Ecuador.

For Ecuador though, by 2001 “perhaps the single largest contributor to deforestation in Ecuador were the Agrarian Reform Laws (1964, 1972) which promoted the colonization of vacant (forest) land as the solution to relieve social pressures caused by inequitable (feudal) land distribution, while expanding the agricultural frontier and subsidizing the growth of export-oriented industrial agriculture. The “Green Revolution” was included in the Agrarian Reform package which the U.S. government sponsored throughout Latin America as part of the 'Alliance for Progress' in the 1960’s. The introduction of the Green Revolution technological packet (hybrid seed grown in monocultures, mechanization, chemical fertilizers & pesticides, etc.) has been disastrous in terms of forest removal, soil degradation, contamination from agrotoxics, loss of biodiversity (including native crop varieties and farming knowledge), and growing dependence on external inputs.”

“The Agrarian Reform laws also considered forestland as “unproductive” and thus available for occupation or expropriation. It obliged both property owners (to avoid invasion or expropriation of their land) and colonists (to demonstrate that they were “using” the land as required for claiming title) to clear 50-80% of the forest existing on their holdings. This resulted in the elimination of huge areas of forest to “prove” the land was being utilized. By the time this clause was changed in the early 1990’s most of the Coast has been deforested and unnecessary forest clearing had become (and still is) standard procedure for colonists.”

“Causes And Consequences Of Deforestation In Ecuador” by Jefferson Mecham

Centro de Investigacion de los Bosques Tropicales – CIBT Ecuador - May 2001

http://www.rainforestinfo.org.au/projects/jefferson.htm

Forgotten Times

“For Afro-Ecuadorian communities of Esmeraldas, the agrarian reforms also negatively impacted their traditional collectively held lands. To relieve demographic pressures in other regions, the 1964 and 1973 reforms designated certain areas of Esmeraldas as empty land, and therefore a destination for landless farmers. This designation marked the beginning of an influx of mestizo landless immigrants, known as colonos (colonists or settlers), to the region that would last for decades. Large-scale logging, new highways, and the construction of an oil refinery attracted migrants to the province as well. Colonos arrived from rural areas throughout Ecuador and Colombia, and many came from Manabí, the province located just south of Esmeraldas.”

“These landless immigrants obtained land awarded by the government, sometimes consisting of individual plots of 50 hectares or more. Additionally, colonos purchased ancestral lands that were meant to be communal from individual Afro-descendant families.”

“The legal recognition of Afro-Ecuadorian collective or ancestral titles did not occur as part of the agrarian reforms, so the effect of the government’s titling procedures for colonos was to reduce the amount of land available for Afro-Esmeraldan ancestral communities. In both Esmeraldas and Valle del Chota, land remains at the center of Afro-Ecuadorian communities’ historical and present struggles. Today’s rural Afro-Esmeraldeños fight against

displacement from their land by commercial agriculture, and extractive industries.”

“Forgotten Territories, Unrealized Rights: Rural Afro-Ecuadorians and their Fight for Land, Equality, and Security” November 2009 - A Report from the Rapoport Delegation on Afro-Ecuadorian Land Rights

https://law.utexas.edu/humanrights/projects_and_publications/Ecuador%20Report%20English.pdf

Ecuador Logging and the Oil Palm Industry

The illegal and extra-legal nature of individual sale of communal land means that little empirical data exists to document the trend. “The logging and oil palm industries were first established in Esmeraldas during the 1950s in the centrally located area of Quinindé. The process of clearing land for lumber and installing oil palm plantations has since expanded into northern Esmeraldas and has sharply increased in the early twenty-first century. The logging and oil palm industries are linked together in a way that contributes to the loss of Afro-descendant ancestral territory.”

“In the first of a two-part process, timber companies contracted with middlemen to clear land. Oil palm cultivators soon followed, and, using financial incentives and violence, pressured small farmers to sell or vacate the newly cleared lands. The loss of forests began in the 1960s, and by 1990 approximately ninety percent of Ecuadorian forests west of the Andes Mountains had been logged.”

“Along with indigenous people, Ecuador’s Afro-descendants experience greater poverty and inequality than whites or mestizos, impacting education, and health. Longstanding racial discrimination impacts rural Afro-Ecuadorians’ struggles to remain in their territorial spaces. Structural racism represents a central barrier to the effective guarantee of Afro-Ecuadorians’ human rights. Structural racism, refers not only to direct discrimination based on race, but also to broad social and institutional practices that cause the unequal distribution of resources and social opportunities along racial lines.”

According to the community members that the 2009 Rapoport Delegation on Afro-Ecuadorian Land Rights met with in northern Esmeraldas, “both the palm oil mill effluents (POME, liquid waste) and the air pollution generated by the extraction of palm oil has lead to further environmental degradation, observed by the death of fish populations in nearby rivers, and rashes on the bodies of people who bathe in these waters. At a community forum, the delegation learned specifically of one community that has been severely affected by environmental contamination caused by oil palm cultivation. The community of La Chiquita depends on the river system to eat, drink, bathe, and provide other basic needs; yet, the wastewater from oil palm processing has caused health problems, reduced access to water for consumption and other uses, and inhibited traditional fishing practices.” (“Forgotten Territories, Unrealized Rights: Rural Afro-Ecuadorians and their Fight for Land, Equality, and Security” November 2009 A Report from the Rapoport Delegation on Afro-Ecuadorian Land Rights)

http://www.cornell-landproject.org/download/landgrab2012papers/johnson.pdf

In 2005 the oil palm monoculture expansion in the province of Esmeraldas was 80,000 ha. This represented 38.5 percent of the total area for this crop in Ecuador. The same year for the San Lorenzo canton, oil palm monocultures covered 18,000 ha.

Less than 6 percent remains (broken, polluted, and scattered) of Ecuador's original forests.

What can the consumer assurances of the Certification Industry, and GreenPalm Offsets Certificates, mean? When a product label states that no rainforest is falling today in Ecuador for Organic RSPO Certified Sustainable Palm Oil Products – the agricultural history up 2012-2013 in Ecuador, is riddled with toxic pesticides, indigenous loss of land, food scarcity, (the usual social conflicts and environmental destruction). Logging of virgin forests and road construction are the precursors to drilling for oil, mining, plantations, and settlements.

Cultural Survival puts it this way: “African Palm Oil: Impacts in Equador's Amazon”

http://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/ecuador/african-palm-oil-impacts-equadors-amazon

Speaking of the time period of the 1990's when the pace of Ecuador's deforestation quickened to keep pace along with global competitors: “Fifteen years ago, the areas where the palm oil plantations are now located were trackless virgin rainforest. The forests provide building materials for their homes, wood for canoes, palm leaves and vines for baskets, and a place together wild foods and medicines and to hunt small game. The rivers supply them with water and protein from fish, caimen and turtles.”

“The Indians also depend on extensive areas of rainforest to support their swidden form of agriculture, which is ideally suited to the tropical rainforest. Their small forest gardens, called chakras, use only one to two hectares of land and require no pesticides or fertilizer. A wide variety of crops are planted together rather than in rows. By intercropping these plants, plant-specific pests are controlled and the different root systems avoid competition for nutrients. Finally, this multi-layered garden canopy, which mimics the structure of the surrounding rainforest, helps to break up the impact of the rainfall and minimize erosion. After a couple of years a new garden site is cleared and the old garden is left fallow, allowing the forest to regenerate.”

In the 2004 court case favoring Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadoran Communities: “The beginning of the oil palm industry in Ecuador dates to the late 1950s. However, it is in the 1990s when the oil palm monocultures expanded largely in the Northern provinces. Since then, large-scale oil palm cultivation has critically damaged the local environment as well as having a negative impact on the health of oil palm workers and the community members who are directly exposed to the agrotoxins in their daily water supplies.”

“Within this context, in 2004 two communities (the Awa indigenous community of Guadalito and the Afro-Ecuadorian community of La Chiquita) concerned that the oil palm industry was poisoning their bodies and livelihoods, took legal action against four oil palm companies and the Environment Ministry. The lawsuit was supported by scientific data which demonstrated the contamination of water supplies.”

“Biodiversity loss, food insecurity, soil contamination, soil erosion, deforestation and loss of vegetation cover, surface water pollution and decreased water quality, groundwater pollution or depletion, visible and unknown health impacts, also increases in violence and crime, loss of livelihood.”

August 22, 2014 update: Despite the fact that the Ecuador High Court ruled in favor of the communities, “the Ministry of the Environment has not taken the effective corrective actions demanded by the Court's resolution, specifically those related with the restoration of the contaminated environment as exhorted by the jury. The state has failed to monitor and enforce companies compliance with the law.” (Earth Justice Atlas)

http://ejatlas.org/conflict/guadalito-y-chiquita-against-oil-palm-companies-ecuador

It was nine years after the Ecuador High Court's decision, that there came the 2013 Trafficking in Persons Report from the US State Department stating: “Monoculture oil-palm expansion is also affecting Afro-descendant and indigenous populations in Ecuador; particularly in the biologically diverse Cayapas-Mataje Ecological Reserve in Esmeraldas. Local activists and human rights groups report oil palm companies are increasingly moving into the northern coastal province of Esmeraldas, which is a traditional Afro-Ecuadorian zone. This is having a direct social and environmental impact on Afro-descendant and indigenous Awá and Chachi villages, including land appropriation.”

http://www.state.gov/j/tip/rls/tiprpt/countries/2013/215454.htm

The oil palm saga continues.

“CO2lonialism and the ‘Unintended Consequences’ of Commoditizing Climate Change: Geographies of Hope Amid a Sea of Oil Palms in the Northwest Pacific Frontier Territory-Region of Ecuador”

“Development projects surround and infiltrate the Indigenous and Afro-ecuadorian ancestral territories of the canton of San Lorenzo (Esmeraldas Province), located in the “Northwest Pacific Fronter Territory-region of Ecuador.”

In "Geographies Of CO2lonialism And Hope In The Northwest Pacific Frontier Territory-Region Of Ecuador" (2010) author Julianne Adams Hazlewood asks the question “to what degree the Ecuadorian state’s support and investment in oil palm plantation expansion designed to meet biofuel crop demands in the coastal rainforest regions, results in the rearrangement, and often times, devastation of Indigenous Awá and Chachi and Afro-ecuadorian communities’ natural and human geographies. It also inquires into the Ecuadorian government’s recently approved (October 2008) state level conservation incentives project called Socio-Bosque (Forest Partners) developed to do the following: protect the rainforests and its ecological services, alleviate poverty in rural areas, and position the country as an ‘environmental world leader’ for taking concrete actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from avoided deforestation. Socio Bosque claims to be progressive and even revolutionary, but may enact new forms of exploitation and governance in Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian territories that are specific to time and place, but are enduringly colonial.”

“Nevertheless, (Geographies Of CO2lonialism And Hope) also highlights geographies of hope by demonstrating that, contrary to the surrounding sea of monoculture oil palm plantations and the CO2lonial air of contradictory laws in relation to biofuel and ecological services development, Awá, Chachi, and Afro-Ecuadorian communities maintain sustainable practices and enhance agricultural diversity within their territories. Additionally, it emphasizes the emergent place-based social movements in relation to defense of their territories and identities; Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian communities avoid conflict pressures by creating interethnic networks. By casting social nets between their territories, their communities stay connected and, together, defend their rights to territorial self-determination and Living Well and the Rights of Nature.”

Some Chapter headings in this very personal account from inside Ecuador:

“Geographies of Terror and Violence and Research, Hope, and Responsibility; Geographies of Hope: Establishing a Territory of Peace; Casting Inter-ethnic Social Nets across a Sea of Oil Palms in the Northwest Pacific Territory-region of Ecuador.”

“Communities surrounded and infringed upon by development processes, in this case, oil palm plantations, choose to assert themselves in a particular way and take on a certain identity, or perform as agents of transculturation to take action to make a change in their lives and negotiate development (and conservation) schemes. In order to do so, they often make claim to a certain essentialized ancestral identity, although the lifeworld they are drawing from inevitably has much deeper roots, and thus, various routes that are much more complex and complicated. It is at the crossroads of these roots and routes where people rise up and defend what they call home.”

“Hybrid networking these crossroads or hybridizations of active negotiations, can emphasize a ‘relational becoming’, but in order to be effective, must be put into actions that lead towards actual laws, structures, and law-supporting practices that reinforce the “struggles of the poor” and help them defend themselves against geographies of violence, terror, and fear that are implemented via oil palm plantation expansion. Geographies of hope, then, necessarily work towards an increase in a rights-based consciousness and practices basically because it has to.”

“Unfortunately, immersed in geographies of terror and violence, communities inspired by revolutionary impulses need state and international support to stand up to multinational geopolitical interests. In looking at geographies of hope as peace-with-justice processes, they obligate implementation of these rights by establishing laws and structures that actually respect rights, such as the constitutional rights of the right to Living Well, Plurinationality, and the rights of Nature (2008 Ecuador Constitution).”

Julianne Adams Hazlewood, "Geographies Of CO2lonialism And Hope In The Northwest Pacific Frontier Territory-Region Of Ecuador" (2010) 321 pages

http://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/52/

Click on download link to view as PDF. The file is 240 MB. Footnotes and extensive citations of descriptive content make up half the document, great images.

Much of what is documented by the author may by contrast, help to explain more clearly, the similar claims of oil palm products manufacturers and distributors of palm oil products that assure us: “The region in Ecuador where our Organic Red Palm Oil is grown has numerous small family farms, averaging 10 hectares (about 25 acres), interspersed throughout the regional forests. These subsistence farms were planted many years ago and are now being worked by second and third generation farming families. Palm oil grown in Southeast Asia is associated with destruction of rainforest and orangutan habitat. It is important to note that orangutans do not live in Ecuador and our red palm does not contribute to deforestation or habitat destruction.”

Interesting enough, the farming families (smallholders, smallholder farmers) are usually surrounded by, and even can be part of the legal oil palm plantation real estate network of expansion (defined so well in the Indonesian smallholder law passed months before Jacowi ascended to the Presidency). That a different interpretation of colonialism appears in different countries where palm oil cultivation continues to expand rapidly, appears to be a function of dominant culture national interpretation, International cultural exchange, national political instability, local NGO's, Indigenous cultures persistence, global trade agendas, and market function.

“Modern oil palm cultivation is generally characterized by large monocultures of uniform age structure, low canopy, sparse undergrowth, a low-stability microclimate and intensive use of fertilizers and pesticides. The oil palm tree generates fruits from the third year, with yield per tree increasing gradually until it peaks at approximately 20 years. Hence, oil palm plantations are typically destroyed and replanted at 25 to 30 year intervals. The process of palm oil production tends to reduce freshwater and soil quality, and adversely affects local communities which are dependent on ecosystem products (such as food and medicines) and ecosystem services (such as regulation of the hydrological cycle and soil protection) provided by the forests.” Taken from: “Oil Palm Plantations: Threats And Opportunities For Tropical Ecosystems - Thematic Focus: Ecosystem Management and Resource Efficiency” - UNEP Global Environmental Alert Service (GEAS) December 2011

http://www.unep.org/pdf/Dec_11_Palm_Plantations.pdf

Size of Farm, Market Destination, Land Use Changes in Ecuador

The size of small farms or smallholder farms varies as generations of family members remain, the original 'smallholding' is sub-divided, and allowing for the crops to be grown.